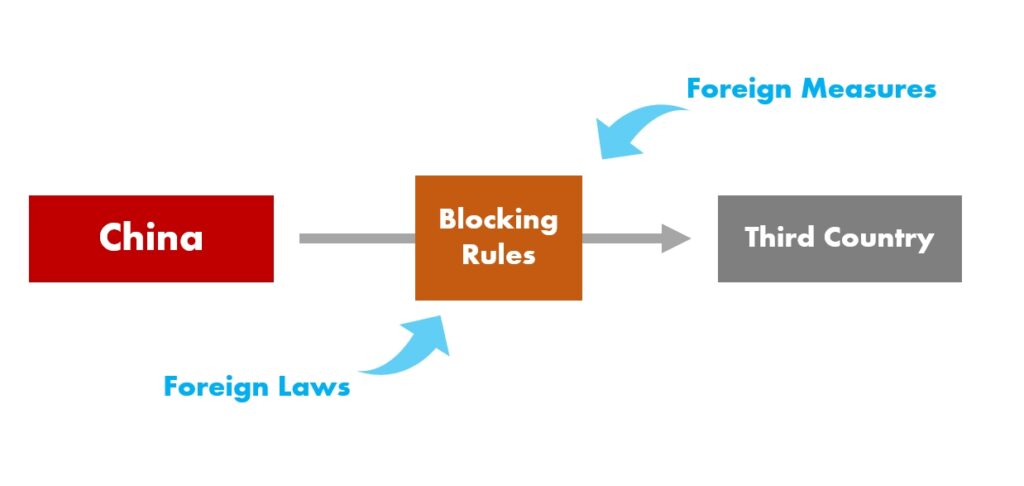

Since the Ministry of Commerce issued the Rules on Counteracting Unjustified Extraterritorial Application of Foreign Legislation and Other Measures (hereinafter referred to as the “Blocking Rules”) last Friday, interpretations from professionals in the legal and related fields have been abundant. Due to the overly broad definitions in the provisions, there are differing and even conflicting views on its scope of application.

While the author is not a legal practitioner, I have tried to streamline the analytical framework. In brief: Where do the main points of divergence lie in the various interpretations? How can we intuitively visualize these differences? This article attempts to approach the scope of the Blocking Rules from a different perspective.

Setting the Stage: Tool Born from Necessity

As the saying goes, “To do a good job, one must first sharpen one’s tools.” The creation of any tool stems from necessity. First, we simplify the meaning of the Blocking Rules into more intuitive graphical relationships.

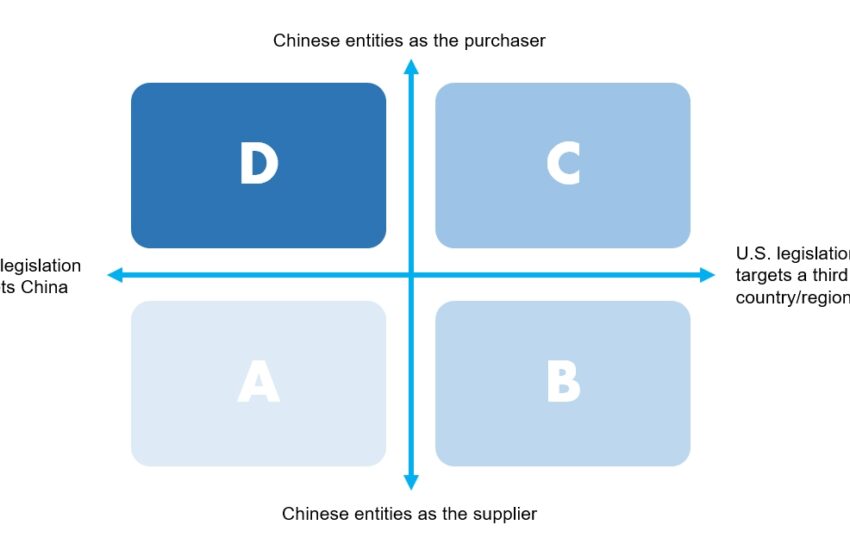

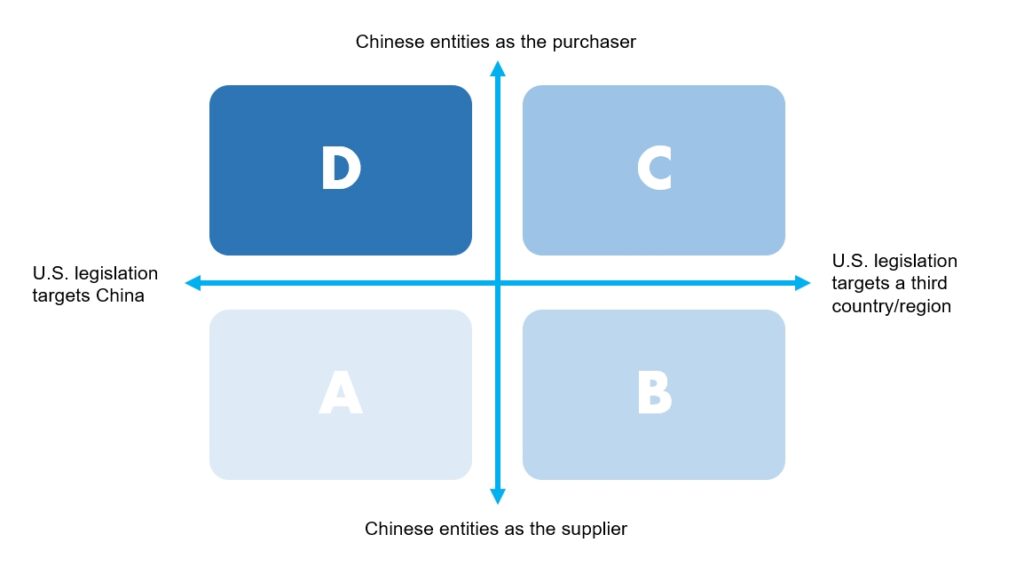

We further break the graphical relationships into two questions:

- Does the foreign legislation target China or a third country?

- Is China a supplier or a purchaser in the transaction?

Given the current context, using U.S. legislation as the “foreign law” variable most easily resonates. Therefore, the following analysis uses U.S. legislation as an example. By using these two questions as the horizontal and vertical axes, we arrive at the following matrix divided into four quadrants (A, B, C, D):

Quadrant A: U.S. legislation targets China, and the Chinese entity is the supplier

For instance, the U.S. Customs and Border Protection’s recent import ban on all cotton and tomato products from the Xinjiang region, as well as previous restrictions on WeChat and TikTok usage in the U.S., may fall under this category. These cases are not covered by the Blocking Rules but may be countered through measures like the Unreliable Entity List Provisions issued last year by the Ministry of Commerce or other diplomatic actions.

Quadrant B: U.S. legislation targets a third country, and the Chinese entity is the supplier

In this context, Chinese entities and third-country entities may have normal trade relations. However, U.S. sanctions against the third country may result in penalties or sanctions against Chinese entities that continue to supply goods or services to the third country, i.e., “secondary sanctions.” For example, in November 2017, the U.S. Treasury claimed that China’s Dandong Bank participated in North Korea’s illicit financial activities, leading the U.S. to ban financial dealings between U.S. institutions and Dandong Bank while prohibiting its overseas branches from cooperating with Dandong Bank.

This scenario is generally considered within the scope described in the Blocking Rules. In such cases, the affected Chinese enterprise may report to the mechanism led by the Ministry of Commerce. If deemed an unjustified extraterritorial application of foreign law, the mechanism may issue a prohibition order, rendering the U.S. sanction invalid under Chinese law. Entities complying with U.S. sanctions may face compliance risks under China’s prohibition order.

Quadrant C: U.S. legislation targets a third country, and the Chinese entity is the purchaser

In this scenario, a supplier may halt supplies to a Chinese entity due to concerns over compliance with U.S. law, fearing that the goods may be re-exported to the U.S.-sanctioned third country. The supplier could be a Chinese company, a U.S. company (or its Chinese subsidiary), or an entity from another country.

This scenario is also considered within the scope of the Blocking Rules. The Chinese enterprise can report to the Ministry of Commerce. The supplier, upon the issuance of a prohibition order, may either comply with Chinese law or continue following U.S. law while risking legal consequences in China.

Quadrant D: U.S. legislation targets China, and the Chinese entity is the purchaser

This quadrant represents the primary point of contention regarding the Blocking Rules’ applicability. It can be further divided into three situations:

- Supplier is a U.S. entity: The U.S. restricts key Chinese enterprises from importing critical components under export control regulations for reasons such as national security. U.S. entities refuse to trade with Chinese entities due to compliance with U.S. law, effectively “cutting off supplies” to China.

- Supplier is a Chinese entity (including U.S. subsidiaries in China): For example, a U.S. company’s subsidiary in China halts supplies to a Chinese company under orders from its U.S. headquarters, citing compliance with U.S. export controls.

- Supplier is a third-country entity: A third-country entity complies with U.S. sanctions and refuses to trade with Chinese entities, leading to “supply disruptions.” For instance, following U.S. sanctions against Huawei, third-country companies like Samsung Electronics ceased semiconductor exports to Huawei without U.S. approval.

Are These Situations Covered by the Blocking Rules? Divergent Opinions

- Fangda Partners’ article: Situations 1 and 2 may not fall within the literal scope of the Blocking Rules as they do not involve third countries. However, if a U.S. or U.S.-affiliated company’s supply disruption indirectly impacts a Chinese company’s trade with third countries, the Blocking Rules might still apply. In situation 3, where a Chinese entity listed on the SDN list faces a trade disruption with third-country entities, the Blocking Rules apply.

- Frank Pan (senior international trade lawyer): If foreign measures specifically target trade with Chinese entities, they are outside the Blocking Rules’ scope but fall under the Unreliable Entity List. Thus, situations 1, 2, and 3 are not covered.

- “International Legal Affairs” article: The Blocking Rules presupposes that “China does not recognize the extraterritorial effect of foreign laws within its territory.” Under this principle, foreign laws should not bind economic entities in China, including foreign subsidiaries operating domestically. Therefore, even if the Blocking Rules explicitly reference “third countries,” they implicitly reject the applicability of foreign laws on Chinese soil.

Interestingly, an article by King & Wood Mallesons published in September last year argued that the Unreliable Entity List cannot counteract supply disruptions caused by domestic Chinese subsidiaries of foreign entities (situation 2). It suggested creating targeted “blocking legislation” to address foreign export controls, supplementing the Unreliable Entity List. Perhaps the authors were unaware at the time that the Blocking Rules were already in the making.

Complex Realities in International Trade

International trade is far more intricate than theoretical models; the interplay between parties is much greater than a simple 2×2 matrix. The charm of globalization lies in its interconnectedness. For this reason, most stories in this domain are neither black nor white, nor is there a single path forward.